Amid one of the largest climate crises facing some Brazilian regions, such as the floods in the country’s South and the drought of the Madeira River in the Amazon, society is taking a closer look at one of our planet’s most important assets, water.

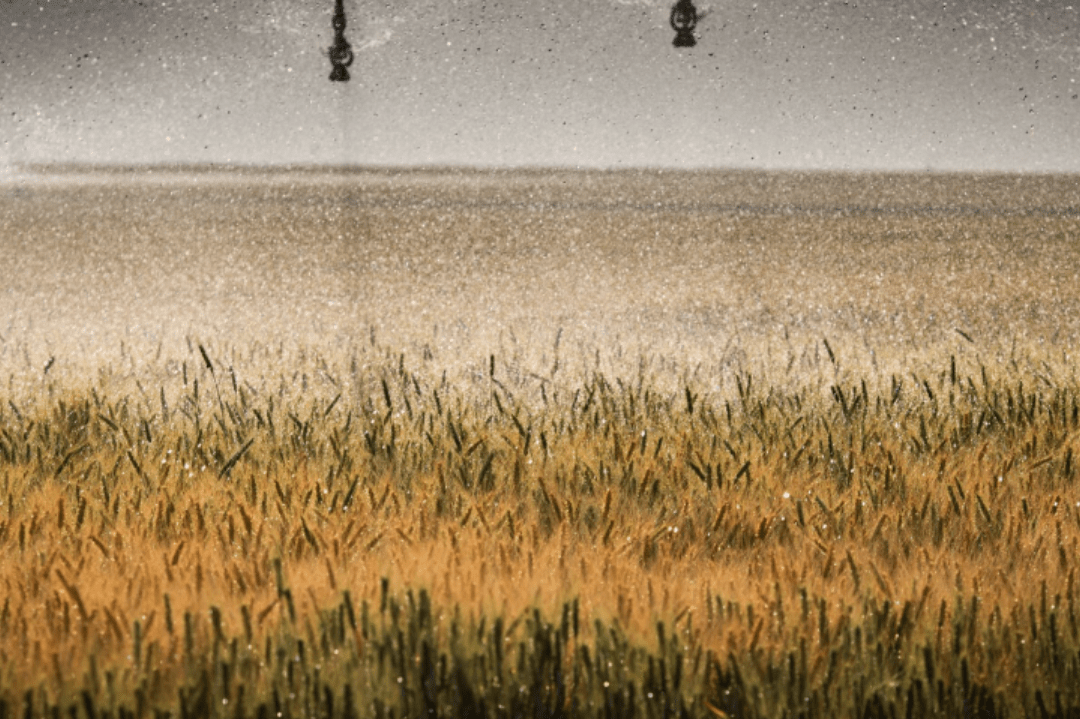

Making the best use of this precious resource, meeting the most diverse needs of the population, and preserving water resources and the environment have become daily issues in the world news. For the agricultural sector, the worst-case scenario related to climate change is the restriction of food production, leading to water and consequently food insecurity.

According to Pakistani scientist Rattan Lal, laureated with the Nobel Peace Prize and the World Food Prize, “When our stomach is not full, there can be no peace. There can be no peace if there is hunger and malnutrition. I believe that what Brazil and South America are doing in agriculture is promoting peace, and other countries should do the same.” He also highlighted that Brazil can be a model of global leadership concerning the use of soil as a carbon storage for positive agriculture. Sustainable soil management in agricultural production also results in water management and improves the water security needed for the food security of the world’s population.

In Brazil, the Agribusiness Confidence Index (IC Agro) survey found that the weather was seen as the most significant problem farmers face (46.8%), above the selling price of their products, production costs, and occurrence of pests and diseases. The challenges of expanding agriculture are nothing new for the Brazilian farming and livestock sector, given that we already produce under the strictest environmental, labor, water resources, tax, and pesticide laws in the world.

On several occasions, the sector has shown its skill both inside and outside farms, producing more and better, as well as combining production and conservation. Much of this growth is due to agricultural research and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), which has aided in meeting the demands of rural producers and their need to adapt and integrate with the environment. An instance of this development leap can be seen in the last few decades, when we increased our grain production by 560%, from 46.9 million tons at the end of the 1970s to the current 309 million tons in the last harvest, with an increase of only 106% in the cultivated area, yielding savings of more than 188 million hectares. This was possible due to modern technologies and practices implemented by the Brazilian production sector.

Climate change rises as a new challenge. Brazilian farmers have already shown that they are resilient and adaptable to the climate, as seen in crops such as soybean, wheat, cotton and so many others that have been “tropicalized.”

Prepared to respond once again to the call for food security, as well as social and economic growth, the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA) is engaged in three strategies in the face of current and future climate uncertainties, with a focus on mitigating, adapting, and being resilient to climate change. But we go further. CNA believes that farms are the solution to balancing emissions. It is on farms that water is produced, carbon is stored, and technologies recommended in the world’s largest Low Carbon Agriculture Project (the ABC Program) are used—besides, farms also have the potential to provide environmental services.

In any strategy implemented, the rational use of the resource “water” is the main action, and its prioritizing has been part of the reality of farm management for several decades. Initiatives to preserve water sources—be they springs, watercourses, or aquifer recharge areas—have long been part of the activities of Brazilian rural producers who use them directly. The benefits of these actions go beyond the farms’ borders and influence the quality of life of all Brazilians, making food products cheaper, improving the quality of the water that supplies cities, conserving the soil, and—why not—fostering the economy. We must recognize the role of rural landowners in the water cycle, as they provide significant environmental services and put quality food on the table not only for Brazilians but also for the world’s population.

Fighting hunger and poverty will be two of the challenges facing agriculture in the coming decades. It will be necessary to increase food production by 70% by 2050, when the world’s population will increase by 2.3 billion people (FAO, 2009). This scenario shows the need to increase agricultural productivity, which should account for 90% of this growth.

Discussions regarding the forestry code and Brazil’s option to reconcile production and preservation require coherent policies on the use of natural resources. If the legislation hinders territorial expansion horizontally, there is a need for vertical expansion, in areas of economic and established use. The solution to increasing productivity will be, above all, through the intensive use of technology. The use of irrigation technology is an alternative for verticalizing production, a supporter of food security, and a strategic option for increasing the supply of agricultural products in the national and international markets.

Brazil has a great wealth of water resources, accounting for 12% of the world’s freshwater availability, but only 0.6% of our rivers’ water is currently used for irrigation. Brazil’s irrigated area is less than 2% of the world’s irrigated area, with around 8.2 million hectares, of which 2.9 million are used for sugar cane fertigation. This is less than 1% of the national territory. Brazil is among the four countries with the largest potential area for irrigation growth. A recent study carried out by the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ/USP), in collaboration with the Irrigation Secretariat of the Ministry of National Integration and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), pointed out the new trends of irrigated agriculture in the country. Considering the suitability of soils, terrain, climate, and water availability, the study found that Brazil has around 60 million hectares of potential area for expanding irrigated agriculture. This represents twice the area previously estimated, and this potential does not take into account the opening of new areas, i.e., the study only considered areas already open for agriculture and livestock activities.

With this potential, combined with Brazil’s natural vocation to produce all year round, emerging technological alternatives can enhance production sustainability in the face of climatic variation. These will have to be improved and better adjusted in their uses in different production systems and environments. The expansion of irrigation, electrification, rural mechanization, on-farm storage, and improved rural insurance and logistics would be a huge step forward in the face of current and future climate uncertainties.

The main goal of irrigation is to provide feasible ways of managing the lack of water resources available to irrigate crops. Low water availability and irregular rainfall are factors that affect agricultural production. In this sense, irrigation has emerged as an ally in ensuring productivity, avoiding losses and damages for rural producers, while allowing for an increase in food supply and assuring food and nutritional security for the population.

There are still a few issues to be resolved for this potential to be turned into production and ensure food security. In this respect and given the efforts already made by Brazilian farmers, CNA believes that water security is one of the crucial foundations for the development of any country. National water security is directly associated with the management of water availability, which is why it is important to have a state policy in place to promote the construction of structures to collect and store water, especially in the rainy seasons, so it can be used in periods of drought with lower rainfall levels. These structures will guarantee the needed food security, as well as support water security not only for the producers but for Brazil as a whole.

In this sense, sectoral planning that considers growth scenarios and the dialogue among all users is crucial for the country to no longer be affected by crises arising from well-known issues—such as periods of drought—and become a leading actor in the integrated water management, respecting the particulars of each user sector and taking into account the economic, social, and environmental significance of each one. The utmost ideas are to dialogue, understand sectoral differences, and agree, thus ensuring the food security built up over decades of development in Brazilian agriculture.

By Jordana Girardello, Technical Advisor at the Brazilian Agriculture and Livestock Confederation (CNA)